IN C

The Juilliard School

Center for Innovation in the Arts

Edward Bilous, Director

presents

In C

Music By Terry Riley

Edward Bilous, Director

Esmé Boyce, Choreography

William Fastenow, Technology Director

Langdon Crawford, Interactive Technology Design

Kevin DeYoe, Video Systems Design

Sarah Outhwaite, Videography

John Toth, Video Art

ABOUT In C

By RACHEL STRAUS

The myth of the artist producing masterworks in isolation is one of many fantasies, and delusions, that haunt the creative process. Actually,works of art occur through the interaction of ideas and impulses. Think Stravinsky and Balanchine and their development of a neoclassical set of aesthetic values. Consider Wagner and Nietzsche and their championing of Gesamtkunstwerk, the total artwork. In the early 1960s, composer Terry Riley and choreographer Anna Halprin began to perceive artwork as an open system. But this openness wasn’t, to use 1960s lingo, an invitation to let it all hang out. Their compositional systems allowed for a certain amount of indeterminacy, which challenged artists to listen and then to react to each other in real time.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of In C, the groundbreaking, semi-aleatoric musical composition created by Riley. Among In C’s other artistic achievements, it is considered to be one of the first minimalist compositions in Western music. Edward Bilous (M.M. ‘80, D.M.A. ‘84, composition), director of Juilliard’s Center for Innovation in the Arts, saw this anniversary as an opportunity to re-examine, discuss, and rediscover the insights behind the composition’s making. How, asked Bilous, can Riley’s emphasis on communal listening ignite a multi-artist collaboration, especially one that employs recent advancements in technology? This year’s Beyond the Machine festival seeks to answer that question, opening with two performances of In C, on March 26 and 27, and following them with original student works at the four final concerts, on March 28 and 29.

This production of In C features music, dance, film, and multimedia technology. It is structured like Riley’s score, which is composed of 53 cells that will be played in order, with “the visual material — videos of movement cells inspired by the music — organized around the same principle,” Bilous says. And just as the composition of In C was informed by dance, this version employs dance as its departure point.

Riley’s appreciation for dance developed in Halprin’s San Francisco studio in 1961 and 1962. Observing Halprin’s dancers responding to each other in her improvisational-based classes, Riley reacted by making music extemporaneously. According to Janice Ross’s book Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance (2007), Riley found her “intuitive” and “free form” approach to dance “very influential” and said “it was amazing to see how things could develop with just a few simple materials.” Two years later, Riley created In C, one of the first minimalist works. One of its unique

qualities was its consistent/persistent pulse, a feature that would be emulated by minimalist gurus Steve Reich (‘61, composition) and Philip Glass (Diploma ‘60, M.S. ‘62, composition). In C continues to challenge musicians: while the set score of 53 measures gives them the freedom to play one measure as many times as they want, creating group sonority is the difficult part. Performers can only achieve it by listening to each other.

The Juilliard In C project is built around three processes: listening, responding, and interpreting what has been created in one artistic medium in another artistic medium. With dance as the departure point, choreographer Esmé Boyce (B.F.A. ‘09, dance) designed numerous movement cells last November, knowing that they would be interpreted through the lens of a camera. “Unlike live performance,” Boyce says, “these mini dances are now preserved to be viewed and manipulated in any way we choose.” Behind the camera was videographer Sarah Outhwaite, Juilliard’s digital content coordinator and a former Princeton University student of Rebecca Lazier (B.F.A. ‘90, dance). (Somewhat coincidentally, Lazier is also choreographing this year to In C.) In creating videos inspired by In C, the project’s creative development “can be compared to In C’s cells, which pass through many musicians,” Outhwaite says.

In December, Outhwaite’s video cells were sent to intermedia artist John Toth, who uses computer technology as a primary tool for layering visual art, music, sound, and dance into composite artworks. In January, Toth began interpreting and translating Outhwaite’s video work yet again into 53 multimedia cells, which serve as a visual counterpart to Riley’s 53 music cells. Toth’s resulting cells not only combine and reconstruct Boyce’s choreography, which, Toth says, “emphasizes vertical and sagittal planes,” but also employ minimalist motifs, such as image repetition, abstraction, and a formalist sense of unity.

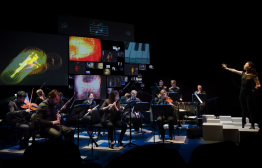

The projection of Toth’s multimedia cells and the 17 to 22 musicians’ live performance of In C at Beyond the Machine won’t be the evening’s culmination. Bilous has trained Brittany Vicars, a tech-savvy fourth-year drama student, to be the project’s video performing artist, and she will project Toth’s 53 multimedia cells in chronological sequence during the performance, choosing from a vast number of electronic tools to vary the ways and number of times they reach the audience. The V.J.’s task is to forge a relationship between Toth’s visualizations and the musicians’ indeterminate progress.

Back in 1964, when In C was conceived, the idea of an open-system performance, in which performance variables were not set and where dozens of performers were making on-the-spot decisions, was deemed radical. In 2014, it continues to be so. But with technology advancements, the ability to understand and listen to one another — before and during a performance — has increased the potential for expression. Juilliard’s In C pays tribute to Riley’s masterwork and to his performance philosophy. It concertizes democracy; it celebrates communication and listening, which potentially deepens and transforms understanding.